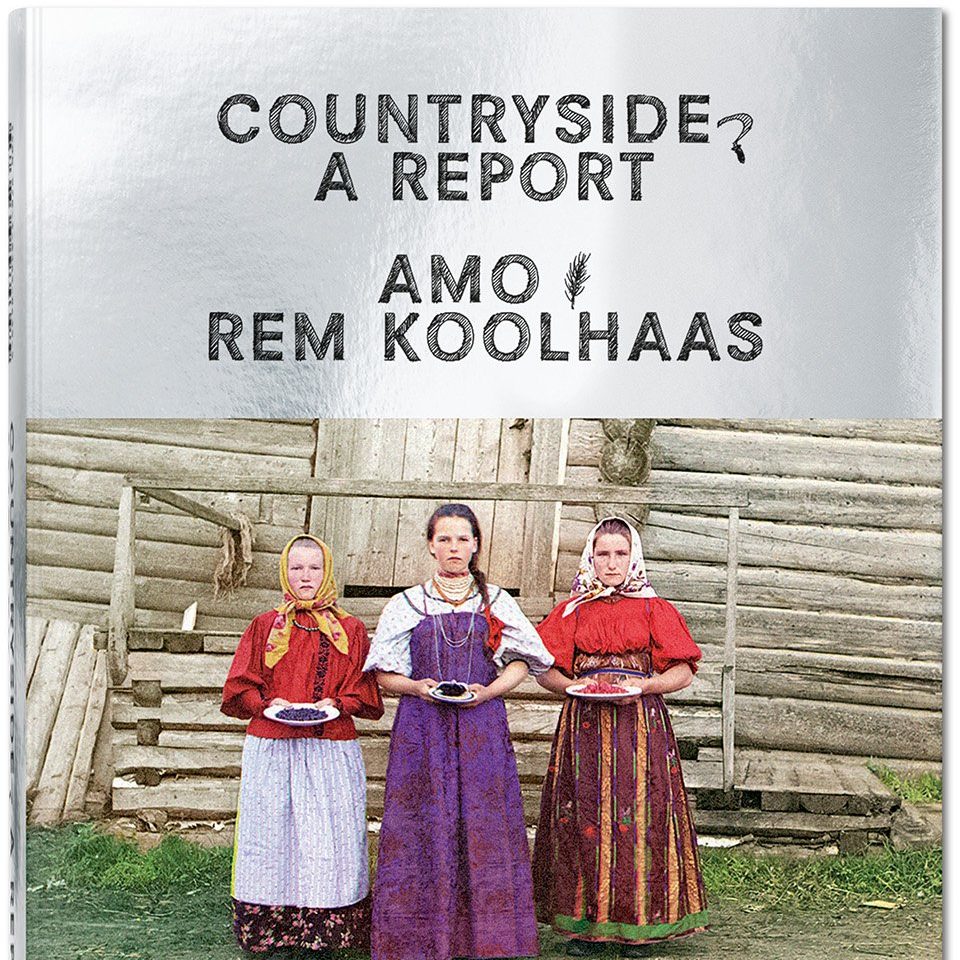

Is that Stalin rolling toward us? Yes, that man-sized cardboard figure on the electric cart in New York’s world-famous Guggenheim Museum is indeed Stalin. But why is Stalin at the Guggenheim? Because the Soviet leader reshaped large parts of the Soviet Union after World War II, and this exhibition is all about reshaping the land. The exhibition – Countryside: The Future, which due to the corona pandemic can only be shown digitally at the moment – spans the countryside, the landscape, the villages, and the history of the world and humanity. The path up the rotunda takes you from the ancient Romans and Chinese through Marie Antoinette and her villas to the conquest of America’s prairies by white settlers; from Hitler’s highways to Chile and Pinochet, and from nuclear fusion to mammoths in Siberia, which can now be bred because the soil, freed of permafrost, has now released their DNA, along with toxic methane gas, unfortunately.

The exhibition – an enormous multimedia installation full of photographs, maps, tapestries, video projections, paintings, patterns, explanatory panels and screens – spans six levels and was conceived by Rem Koolhaas, the Dutch architect, architectural philosopher, former journalist and screenwriter who now teaches at Harvard University, together with his colleague Samir Bantal and Troy Conrad Therrien from the Guggenheim. Also involved were architects from OMA, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture founded by Koolhaas in Rotterdam, as well as students and scholars from Yale University, the Harvard Graduate School of Design, the University of Nairobi, Kenya, Wageningen University in the Netherlands, Waseda University in Tokyo, and the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Perhaps this large number of people involved is enough to explain the wealth of material on display. Koolhaas – who has already designed the Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas – became famous in the U.S. through his book Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan, so there is a certain irony in the fact that a verified urbanist is now enthusiastic about non-urban life. Koolhaas believes the future is not in the city, however, but instead in rural areas, where interesting changes are taking place. In 2014, according to UN statistics, half of the world’s population lived in the countryside. And even the surface of the earth is 98 per cent non-urban. The exhibition’s organisers have a very broad scope here; from the Sahara to the Himalayas to the Barrier Reef, and from a university campus in Silicon Valley to an industrial park near The Hague.