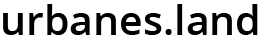

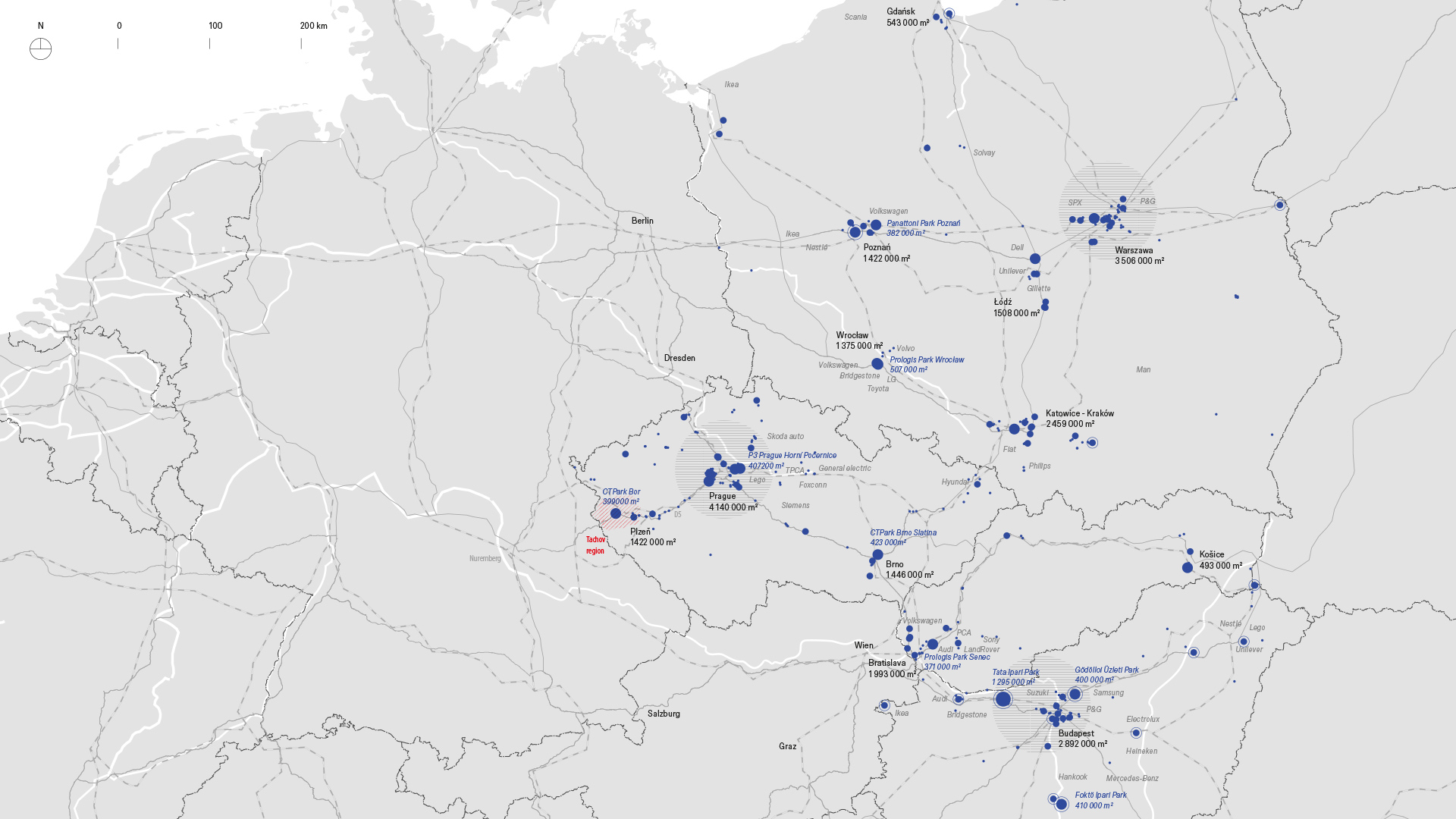

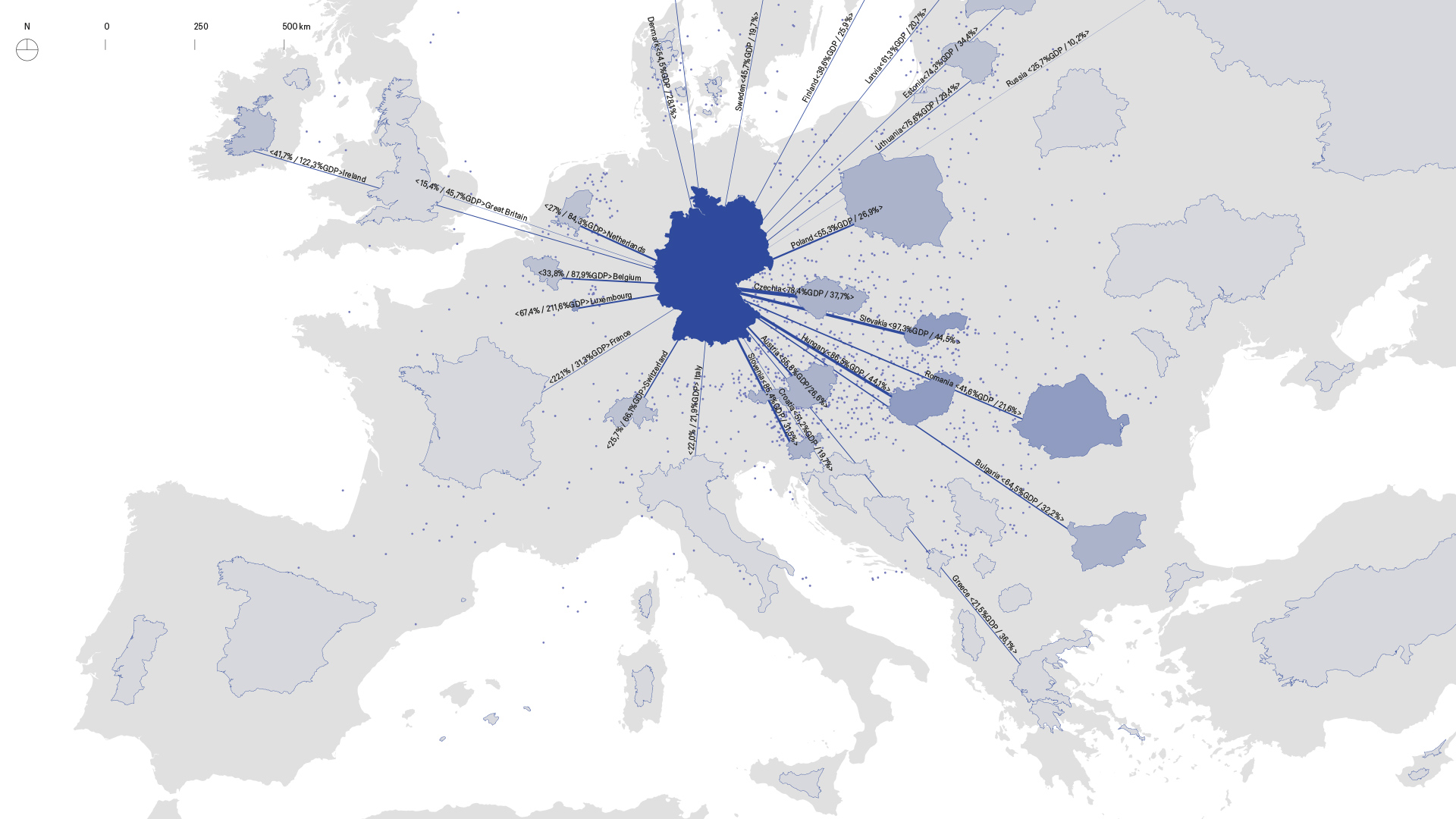

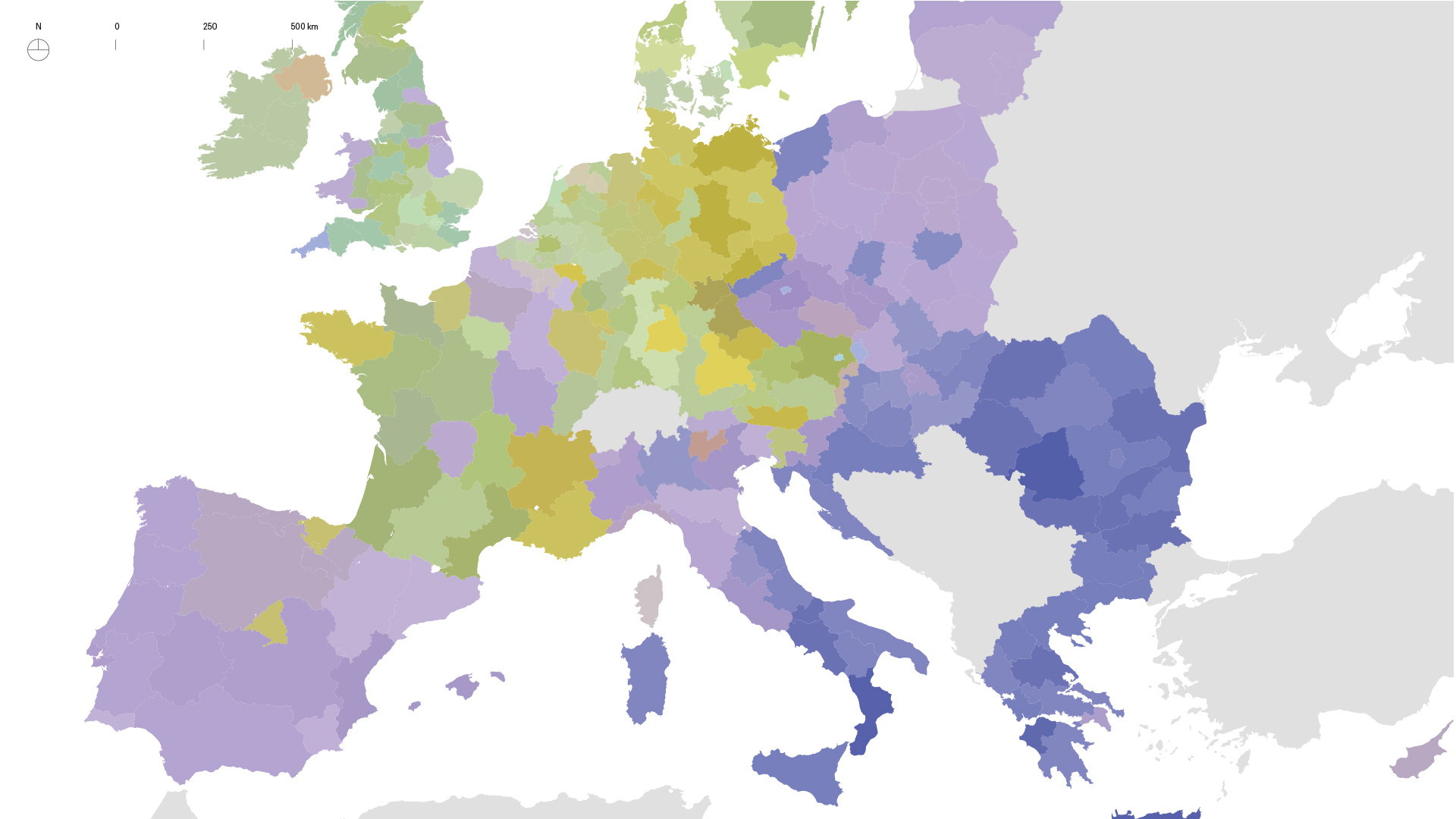

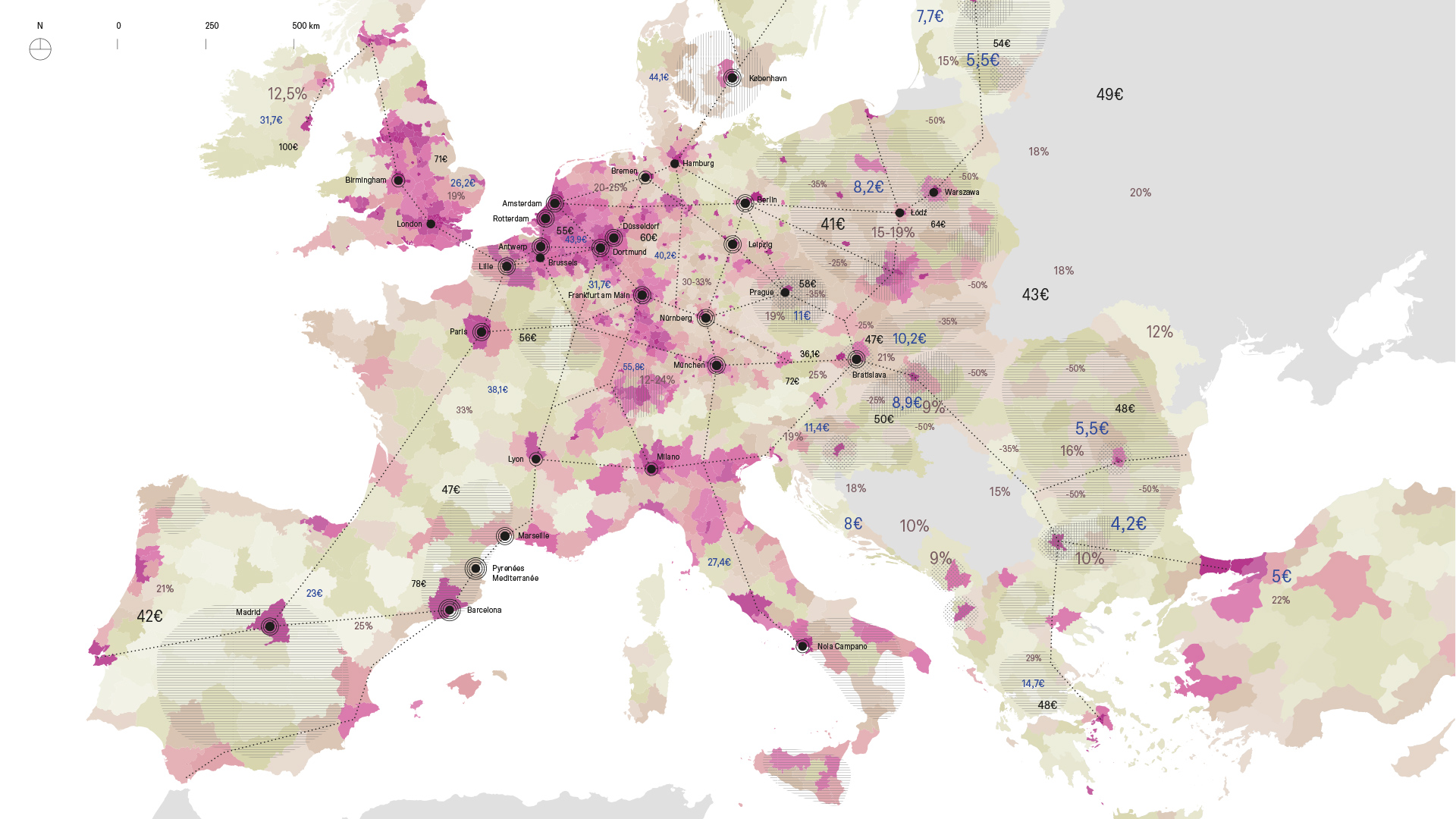

The Architecture of Logistics: In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, a certain type of industry has rapidly developed – an industry that produces nothing. Storing, packaging, assembling, and other ancillary processes of manufacturing and distribution are carried out in extensive logistics parks. These territories have huge effects on the built environment, landscapes, societies, and individuals who live in these regions. Kateřina Frejlachová and Tadeáš Říha on the spatial impact of global supply chains on peripheral territories.

Two contexts of logistics

The shapes and names of urban, suburban and vernacular terrains are capable of carrying meanings that articulate the lives which unfold among them. The territories of continental logistics, with highway networks, truck terminals and especially logistics parks are recognisable almost in no way. They do not intend to be. It is enough that they are measurable.