On your website, you describe the integration of different scales, ranging from landscape to settlement to architecture, from a territory to an individual object. How do you accomplish this in your work?

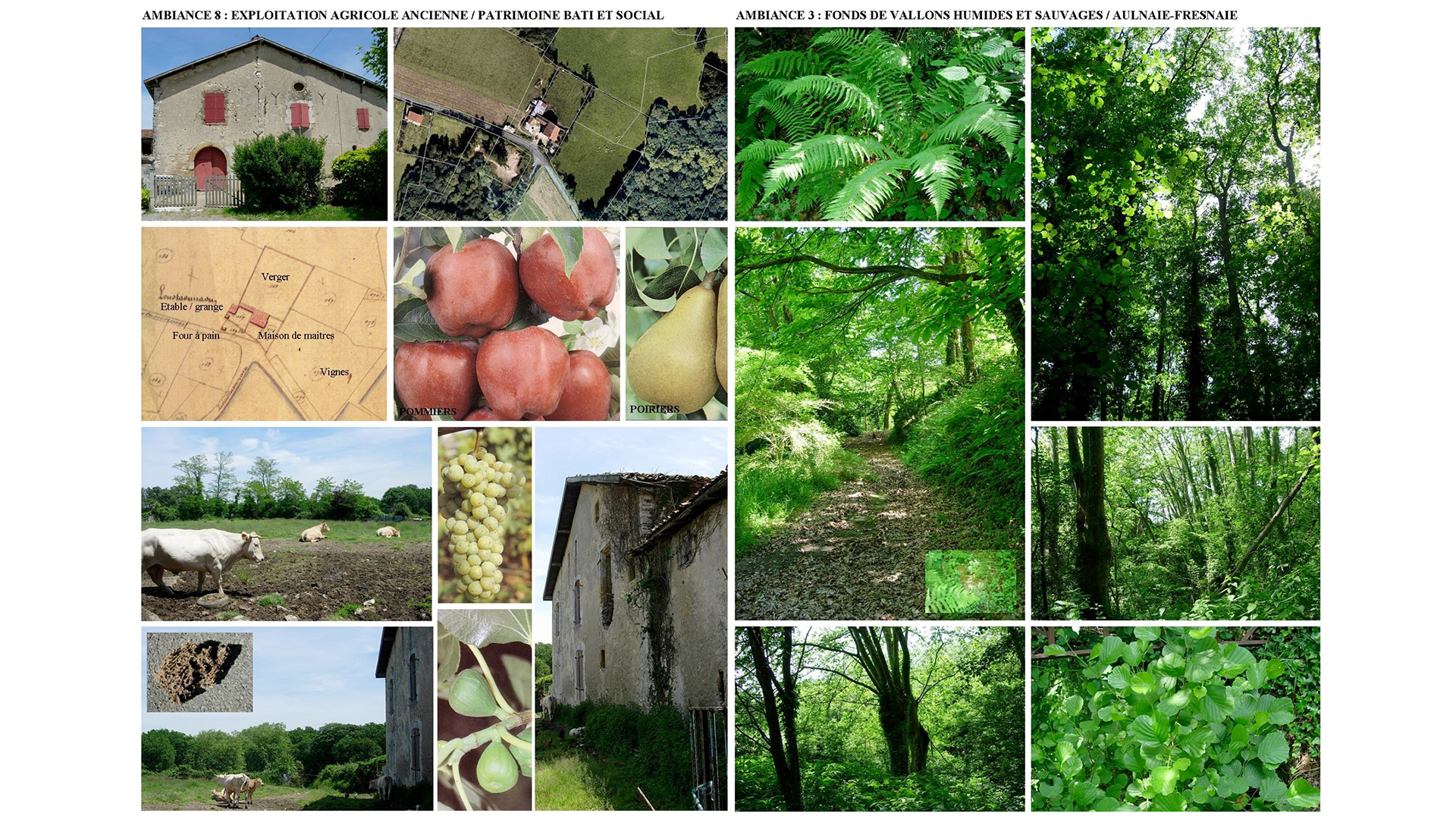

Anna Chavepayre: As I see it, breathing is an activity that is closest to the human scale, and this connects further to the countryside and the old houses that allow for natural ventilation. Here, we don’t require mechanical ventilation or air conditioning. They are fantastic, these old stone houses, enabling natural ventilation throughout the entire year. This scale translates into air and freedom. Therefore, talking about scale means talking about space and time. When talking about scale, we can look at the village again and the small scale it displays. Living and working in a small village means that we can literally eat what grows outside the door. The tomatoes here take up very little space on earth. They don’t require a single square meter of asphalt. Compared to a person who lives in the city and the tomato that person eats, this situation here results in a completely different ecological footprint. Referring to scale, we could also talk about tools. The fact that we currently work with 3D-models and computers in an extensive manner also means that we don’t work at an actual, real-life scale. As a result, we lose the capacity to work at different scales and integrate them. For example, when we work at a large scale, a scale where you can see the whole area, you prioritize what is most important, such as vehicular transport. When we work at a different scale, on the other hand, such as on-site, we don’t lose sight of the details. Yet, I think switching between these scales and integrating them remains a challenge.

In your view, what presently shapes the identity of place and what challenges the historic value of identity?

Anna Chavepayre: The term identity can also refer to something that is identical. It is nothing specific, in a manner of speaking. You need to consider this, because it also leads to problems. When you talk about the identity of the Basque country, “the Basque identity”, then it becomes difficult. One consequence is over-simplification. Compare this to making laws or even formulating architectural rules, how to build properly and so on. In the case of architectural identity, we could say: if it has been in existence since the 19th century, it’s identical. Each village out here, within the area where you can hear the church bell ring, they had their own language, their own architecture, their own laws, everything, and it shows. Every village has its own identity. When you live here, in Bearn, life is completely different than in any other village. But the term identity implies that it is the same for everyone, village by village by village. Even every house has its own identity. Every house has its own, absolutely specific, special place. And that is simply not taken into account. So in a way, this cultural identity means that you don’t do justice to each specific situation. Instead of trying to control everything, why not give some freedom, so that you can do something good on-site?

How does Collectif Encore address this challenge?

Anna Chavepayre: Sometimes I can’t stand it, and I take risks. But the health and lives of people are most important. Having to adhere to the rules that apply is an ongoing challenge. We work in a very specific manner, we do our analysis on-site. It takes a while, but in the end we gain both time and money – because we don’t simply tear down or remove anything. Instead, we use the qualities that exist on-site, or the problems as they present themselves and start to work with them. It isn’t possible to build and make an analysis if we don’t have our feet on the ground. This is where we have to start. We have to be on-site. And you have to be there for quite some time, to really understand the situation. You need to become acquainted with the reasons for why you are doing things there. There must be enthusiasm, your house must be dreamed into reality, otherwise it will actually be nothing. If you don’t dream, wish, want and get excited about what you are going to do, if you don’t have that commitment, then you shouldn’t build anything, simply said.

How do you engage with politicians and local residents, and what interests, processes and co-benefits are in play?

Anna Chavepayre: Those actors who respond really well, politicians, municipalities, ministries, they are just like us. They are ambitious and want to create living places, le territoire. They think it is important to know what we spend the money on. They are sensible people, and everyone tends to agree with what we propose. But people are so interested in building and don’t dare to object. If we dare to say no, then others will follow. Many people have responded to what we say and what we talk about or articles we publish. Even if a project goes slowly, we do what we do with a certain degree of self-confidence – which inspires other people to believe that it is possible to do something different! In this regard, our work inspires hope in people.