You once said, “We can bring back together the things that modernity has brought apart.” Is that the big task lying ahead?

I think it is. I’ve been confronted from time to time in conversations lately almost with a kind of reproach: “You want to make everything the same. One cannot speak of quality if working doesn’t look different from living. You want to impose something like a uniform imprint on the entire region.” But I mean just the opposite. I am convinced that out of this history that we’ve experienced as a society over the last 150 years, out of the artifacts that this history has produced, we have to create a new space, but one that has a lot to do with respect for that history. This implies that new boundaries will be drawn and new fractures created. But fundamentally, the picture will be much more open, permeable and diverse.

The functional separation championed by modernity, work, life, leisure – everything occurring in different places… This reality of life was only possible because of the car-centered city. Today we see this critically – mobility is changing, has to change. What is IBA’27’s position on this?

We are having a bit of a hard time with this topic. There are a lot of emotions attached to it, personal stories, among them stories of successful integration, of prosperity. As soon as you start thinking fundamentally about new forms of mobility, you immediately arouse enormous fears of loss. This is probably also the reason why people have struggled with new ideas and concepts for so long – especially here in this region. At the same time the issues that come with this topic have descended upon the region like a tidal wave. We as the IBA cannot and do not want to be active in all areas and offer solutions. However, we do ask: Is there such a thing as a spatial imprint of possible new systems? We are concerned with the places of mobility, for example. What might a train station look like that has a new meaning in a new transportation system? That’s where we try to take the “B” in IBA seriously, building. How can we create urban structures that are no longer conceived and designed from the perspective of the car, but with more diverse forms of mobility in mind?

This brings us back to good architecture. With it, you can also strengthen urban structures at a regional scale…

That’s right, it also has a lot to do with beauty. I think in the urban versus rural discussion, between the lines you often hear something like: “The cathedral, the opera house, we have to make an effort there.” That is considered important architecture. Historically, we have distinguished between architecture with a capital “A” and with a small “a”. And those buildings with a small “a” simply fulfill their function. For me, the IBA is primarily about a building culture initiative, about an appreciation of all spaces. About the big “A” across the region and in everyday life. Especially here in the Stuttgart region with its strong village structures, which have been able to maintain their intensive qualities for centuries – yet these areas have lost a lot of these qualities in the last seventy years. I am not romantic about this. But I believe that these spaces must regain their diversity, their density, including their social density, and their beauty. Ultimately, it is a democratization of the concept of beauty that lies behind this debate. And an appreciation of the wide variety of forms of life and their different spatial manifestations.

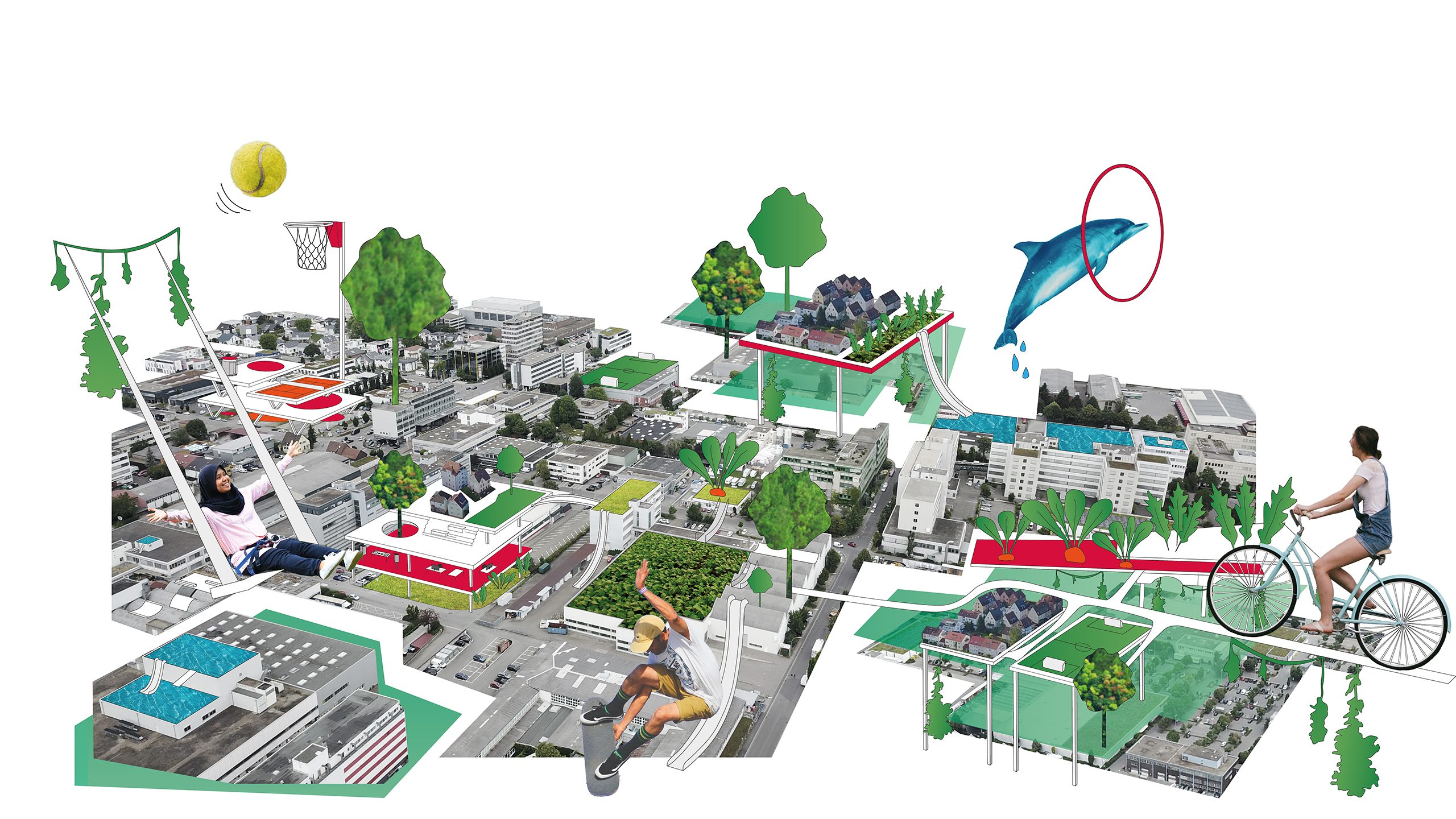

Mr. Hofer, an especially interesting aspect of IBA’27 is that it focuses on extremely diverse spaces and rethinks them – agricultural areas, commercial zones, disused industrial areas, the Neckar River, which is there, but not really accessible to people due to industrial use. Furthermore, the exhibition is about places of movement like train stations and park & ride facilities, it’s about dying city centers, large suburban estates from the 1960s and 70s. In other words, it’s concerned with fringes, places of transition, of being in-between, places at the border, marginal zones….

These fringes you speak of are actually the material from which we can create the future. They are spaces that can be changed, that can be rethought. You mentioned the different kinds of spaces and typologies. Large 1960s or 70s housing estates, for example, are now reaching an age where we can fundamentally rethink them, in many cases have to do so. Often for technical reasons. We have to make them fit for the future, we have to understand these building blocks of different materials, complement them, partially transform them, place them in a new relationship. And above all, we have to look very consciously at the spaces in between. Fringes are like a border where two systems meet. Like a fine-grained web that runs through the region. I’m also thinking of social fringes. Re-thinking cities at these intersections creates new opportunities on both sides of the system. The commercial zone may be endowed with residential functions and qualities; the residential area in turn takes on urban, central functions of meeting, community, and working. The strategy should be to create new relationships here.