Can digital tools enable an exploratory access to distant territories?

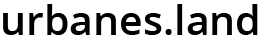

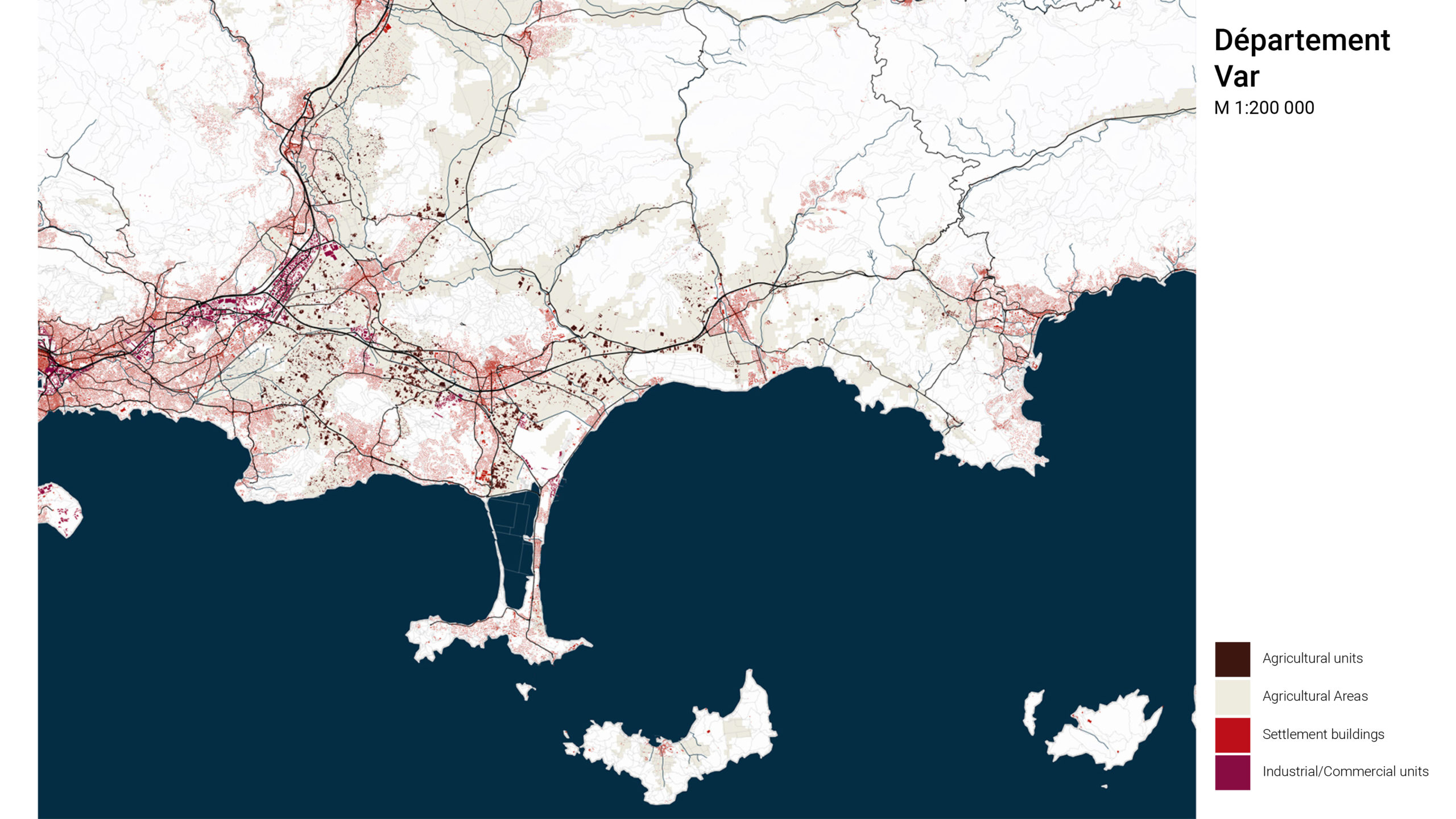

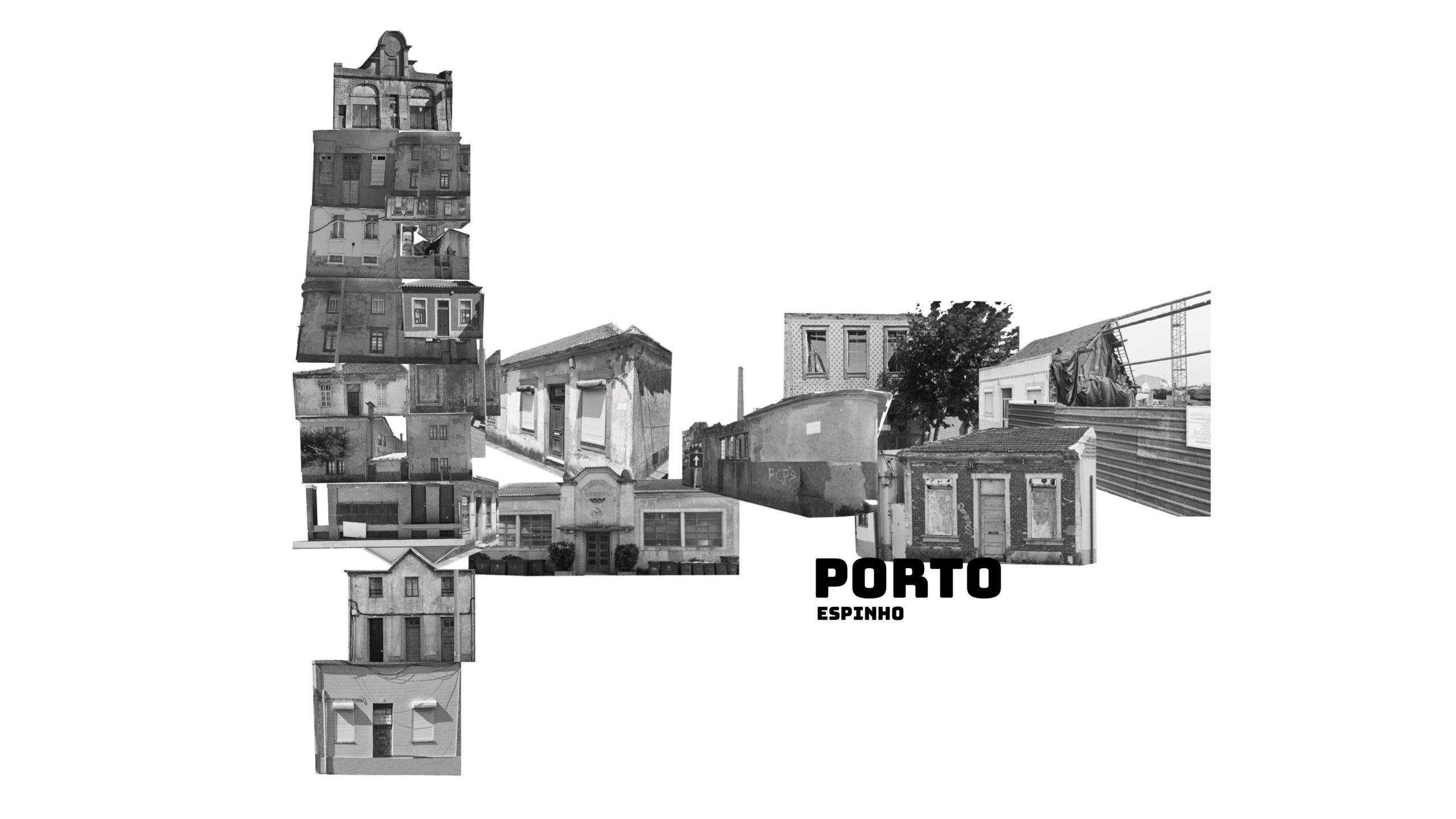

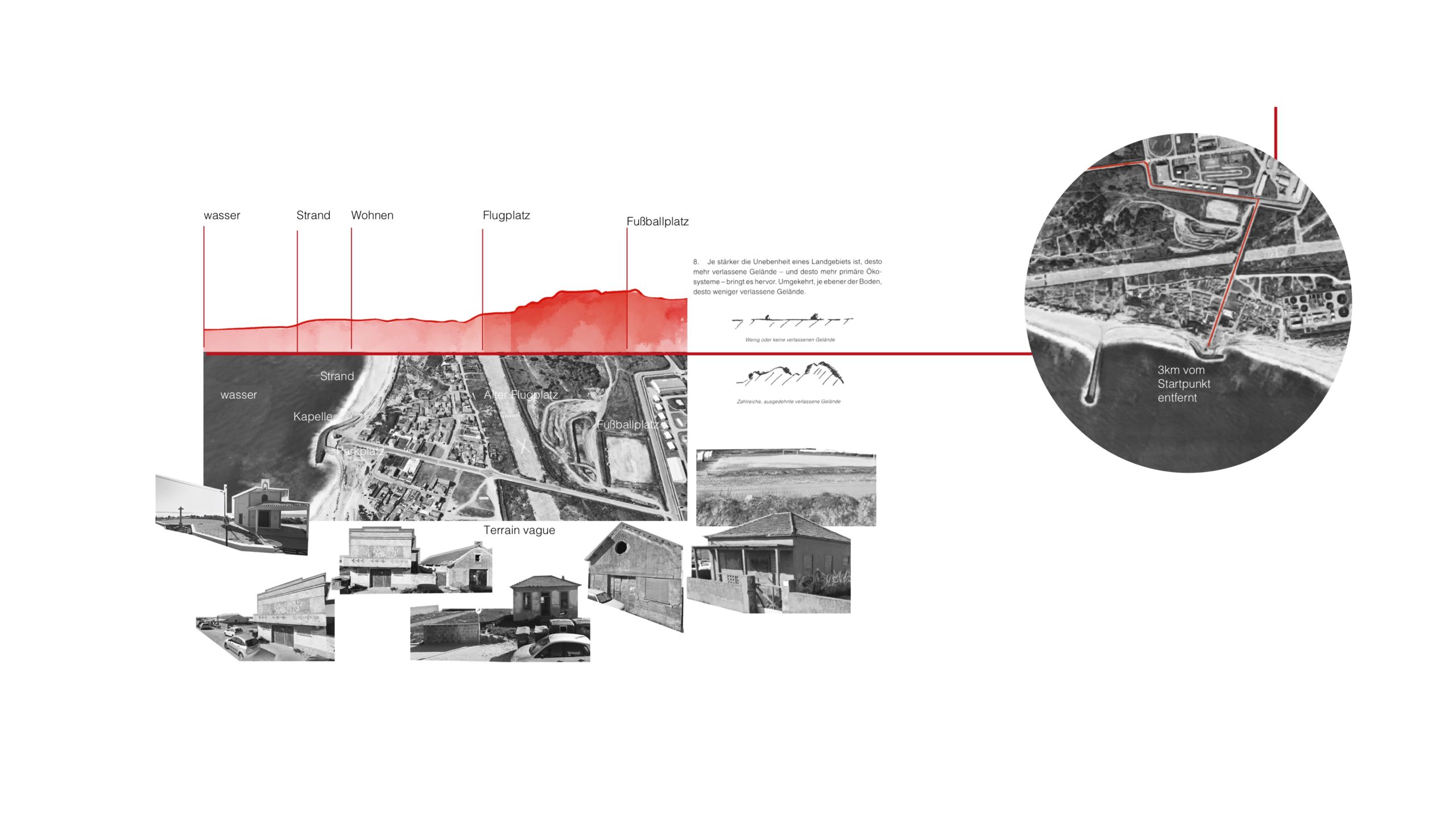

Terrain Vague – In 1995 the Catalan architect and philosopher Ignasi de Solà-Morales Rubio challenged our understanding of urban territory . His seminal article began by looking at how photography’s technical and aesthetic development had decisively influenced our memory, perception and imagination of the modern metropolis. The photographer’s gaze – selective and manipulative – had co-shaped the idea of big cities’ physical constitutions as well as people’s urban lives throughout a century, and from the 1970s on had detected the attractiveness of those urban voids and residual spaces Morales choose to name “terrain vague”. The cloud of meanings the author derived from the semiotics of the term well reflects some of the characteristics we rediscover in the 21st century’s urbanized landscapes between cities: Fluctuating and instable in use, spatially lacking precise confinements, blurred and uncertain in character, but precisely because of this oscillating condition, evocative and full of expectancy.

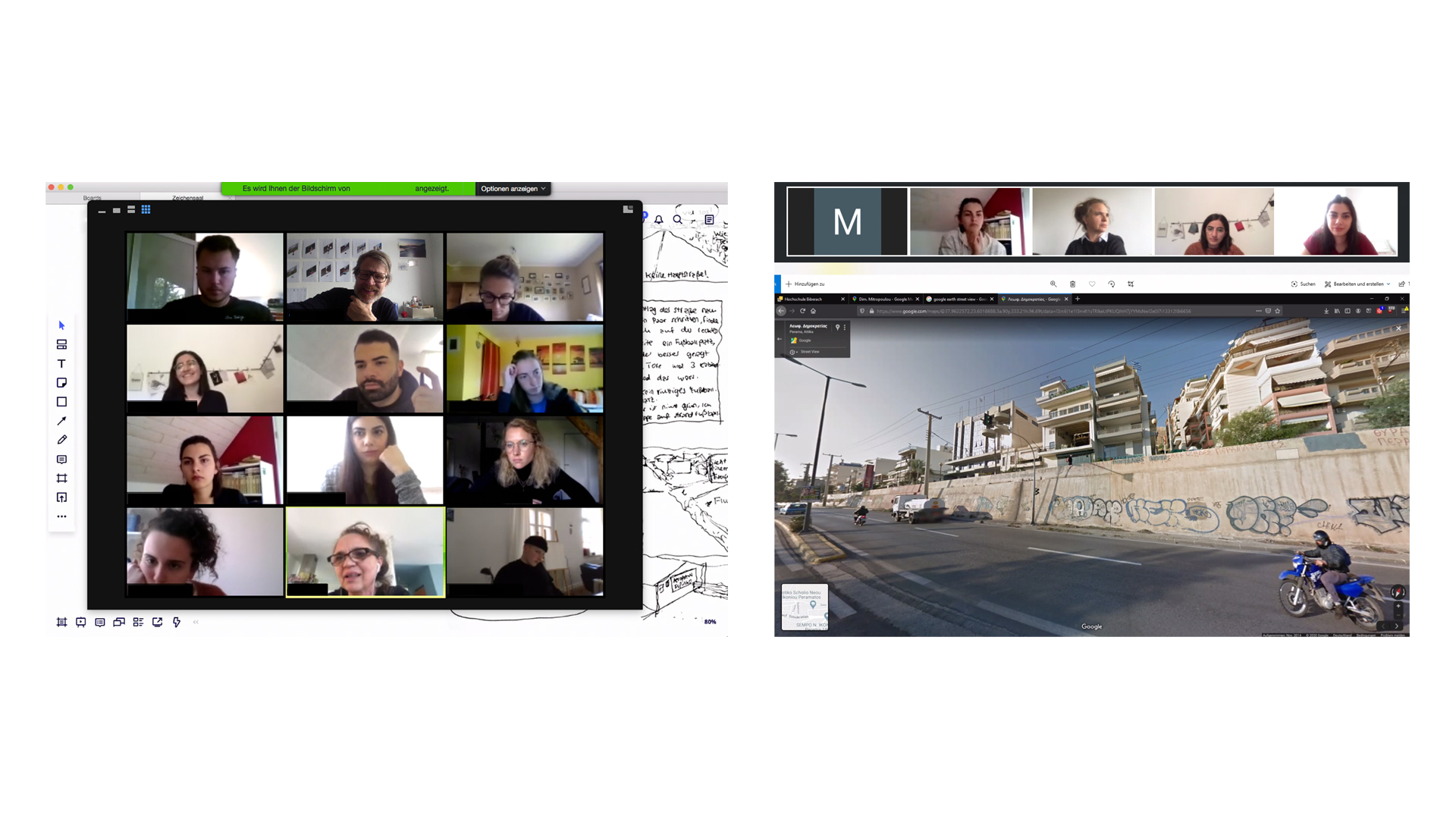

The interest for just this kind of territorial vagueness forms the core of growing research interest . Morales’ article offers a second, equally potent, but still-to-be-discovered legacy, though: It prompts us to rethink the automatic distinction we make between (seemingly) authentic real-life experience and mediated (web)representation of contemporary spatial conditions. In recent years it has become impossible to separate our notion of the (un)built world from omnipresent Google representations. In addition, we as urban researchers have been allowed virtual access to even the most distant places on earth from the comfort of our offices. This being self-evident for some years now, it has hit a new-high as the pandemic experience forced the profession to reflect and innovate their instruments and methods. Starting from where we stand, it is time to seriously allow analysis and research options that stem from open source data, social media and big-data companies or personalized online imageries to become part of an urbanist’s professional toolbox. We argue that accessing online representations can provide new processes, uncover different mechanisms and foster additional ways of understanding when applied within carefully set and strictly controlled methodical frameworks. We should extend the efforts – putting an emphasis on the critical evaluation of and reflection on all these materials to establish a credible base for our findings.